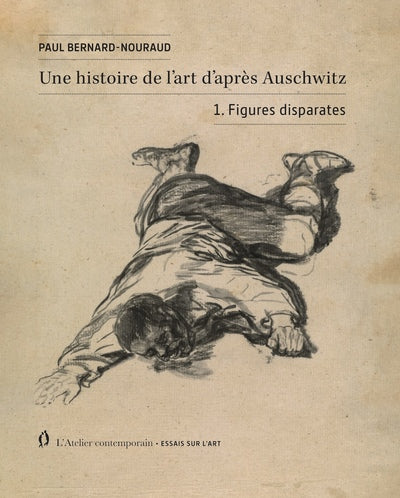

Une histoire de l’art d’après Auschwitz

- Authors: De (auteur) Paul Bernard-Nouraud

- Publishers: WORKSHOP CONT

- Date of Publication: 2024-04-19

- Pages: 648

- Dimensions: 207mm x 165mm

How did Auschwitz break with traditional modalities of representation?

of the human figure? To what extent has this rupture been lodged in the

modernity to the point of going partly unnoticed? Is contemporary art

simply an art after Auschwitz or, more complexly, an art

after the event? These are some of the questions that give rise to

orientation to this History of Art after Auschwitz. The first volume, which

is currently being published, entitled Disparate Figures. It will be followed by two

others: Missing Figures and Configurations. In many ways, this vast

This study also aims to be a counter-history of art, a critical rereading of

foundations of artistic modernity and a genealogy of contemporary art.

This first volume, Disparate Figures, goes back to the sources of this paradigm forged

in the Renaissance which is defined as that of an aesthetic of discernment,

which involves a whole system of theoretical-practical representation. The first

chapter traces in this sense the foundation of the “Discernible Figures” from

of the return of shadows in early 15th century Florence with

Masaccio. Alberti, his contemporary, formalized this system in his De Pictura à

the same period by promoting the idea that a painting represents

History. All the discourse on art after Alberti confirms this idea.

and reinforces it philosophically by considering that the work obeys an idea

that it reveals. This way of investing the work with a function of discernment of

the story and the idea implies another, more tacit but determining one,

both on an artistic and political level: that of discerning fear.

Against this majority trend, a certain number of figures

nevertheless appear to be disparate, as the second chapter suggests.

They attempt to account for three major fears – those of decreation,

of disorder and disaster – to which three phenomena correspond

archetypal – the flood, the plague and the war. In each case, we witness

an antagonism between these events and their reintegration into the orbit of

the aesthetics of discernment. It is this tension that historically produces

disparate figures, of which Francisco Goya would be the great provider. He is also

the one who prepares the ground for figures of another type, which emerge

as for them in the modernist era itself, from the middle of the 19th century to

middle of the last century. These figures are called critics in the

third chapter. In them there is indeed a tendency

self-reflexive which causes them to transform in appearance under the effect of

art for art's sake. However, on closer inspection again, many of them

They more or less explicitly evoke war, or at least the

increasingly warlike historical context in which they are set

(American Civil War, World War I, or Spanish Civil War).

Share